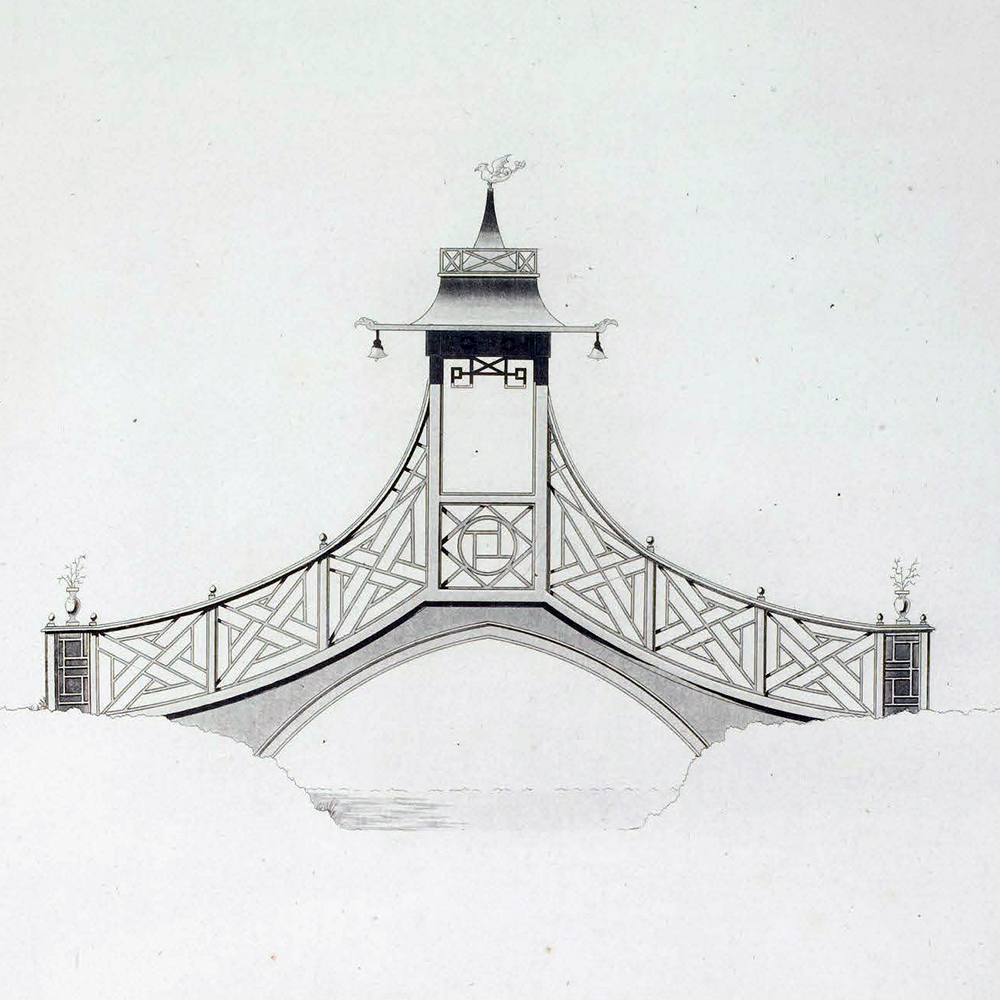

1. The Chinese fret is a key theme in Chinoiserie design and its principles are not always obvious. This series of images attempts to explain its design principles. It is based on a Chinoiserie bridge design published by Becker in 1835, originally designed by one Herr Schaffer.

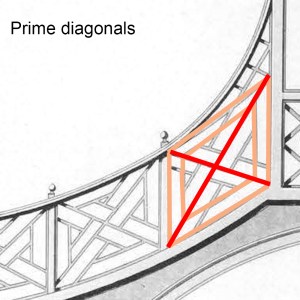

2. Prime diagonals. The fret is very adaptable to a field without right angles and can accommodate a great deal of arbitrariness at the peripheries, but the starting point is always diagonals joining the corners. These are the only members that are continuous between the structural framing of the field.

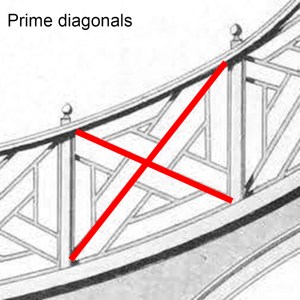

3. Crossing point. The prime diagonals form a crossing point. Everything works outwards from this point, not inwards from the borders of the field where a great deal of arbitrariness is permitted. It is hard to understand what each piece of the fret is doing unless you keep an eye on this crossing point. Yet the crossing point is hard to see: nothing serves to single it out.

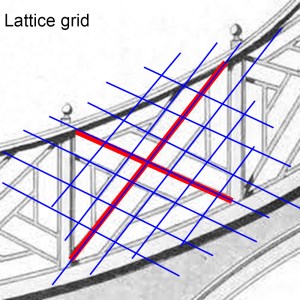

4. Lattice grid. The prime diagonals are expanded outwards by a lattice grid at whatever regular spacing is convenient. This grid is used as required, and disappears from view as the design develops.

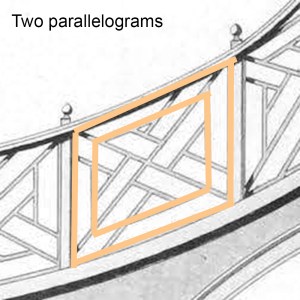

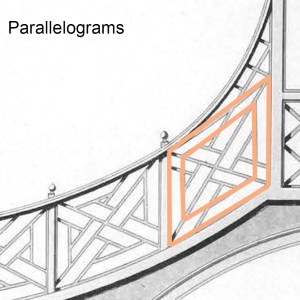

5. Two parallelograms. Superimposed on the prime diagonals are two parallograms that delimit the field. The vertical members will normally be vertical, but the transverse ones can be on a slope but must be parallel to each other. The sides of the outer parallelogram can be curved, as here (making it not strictly a parallelogram), but the inner sides must be straight. The spacing between the parallelograms is established by the lattice grid.

6. The inner pinwheel. Working from the crossing point, the bars of the lattice grid are removed in a regular rotating sequence to form a pinwheel. In the basic fret, as here, this pinwheel extends to the inner parallelogram, but if the lattice grid is finer more complicated arrangements are possible.

7. The outer pinwheel. At the next level of the lattice grid a second pinwheel is created, usually, as here, extending to the outer parallelogram, but if the lattice grid is finer more complicated arrangements are possible.

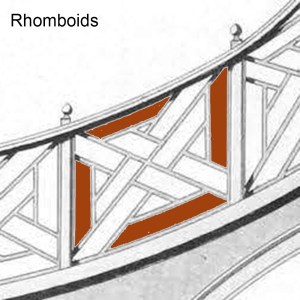

8. Rhomboids. The lattace grid in the spaces between the prime diagonals and the parallelograms are cut away to form four rhomboids. These may intersect with the second pinwheel.

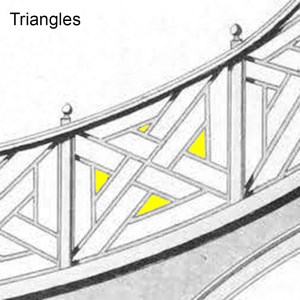

9. Triangles. What is left are triangles, which may, as here, turn out to be of irregular sizes. This does not matter. The Chinese fret accommodates a great deal of irregularity in forms that are left over from the main design actions.

10. Extended irregularity. Parallelograms. The Chinese fret can accommodate a great deal of arbitrariness, as in Becker’s second bay. Here the upper member of the outer parallelogram abandon the handrail, which goes on up. Seeking to follow it, the parallelograms become distorted at the upper right.

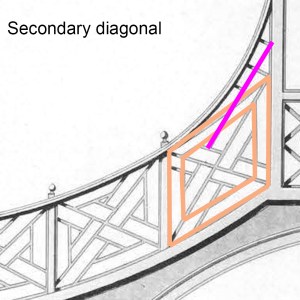

11. Prime diagonals. As a result, the upper right arm of the prime diagonals is extended.

12. Secondary diagonal. This permits a secondary diagonal on the next line of the lattice grid to take on a life of its own and extend into the available space.

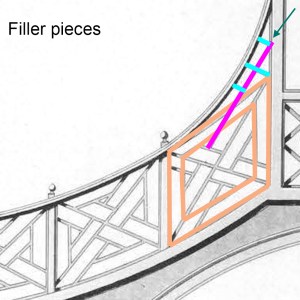

13. Filler pieces. At right angles to the secondary diagonal are short filler pieces corresponding to the lattice grid. They are no real rules about these: they are essentially space fillers. And other forces deflect them off the grid. The uppermost one is moved off the grid to make a neater joint with the secondary diagonal where it meets the extension of the vertical member of the outer parallelogram.

14. Conclusion. The Chinese fret is essentially a way of filling panels. It originates in woodwork but is difficult to execute in wood. It is structurally weak as the only members that continue through to the framing structure are the prime diagonals. The joints are complicated, involving lots of half-laps or mortises and tenons. One has to admire the skill required to execute a Chinese Chippendale glass door frame. It is, however, well adapted to welded steel tube, but in a case like the Becker bridge every joint is at a different angle. As these frames show, the design principle involves three elements: prime diagonals, parallelograms, lattice grid, and pinwheel. It is very well adapted to irregular fields, especially deformed rectangles, as it tolerates asymmetry and at the peripheries decisions can be made empirically and unsystematically. It is at the opposite pole of, for example, the classical arcade, where the rigidity of the arch and the need to control the proportions of columns and entablatures means that a small change in width or height causes everything to change in step.