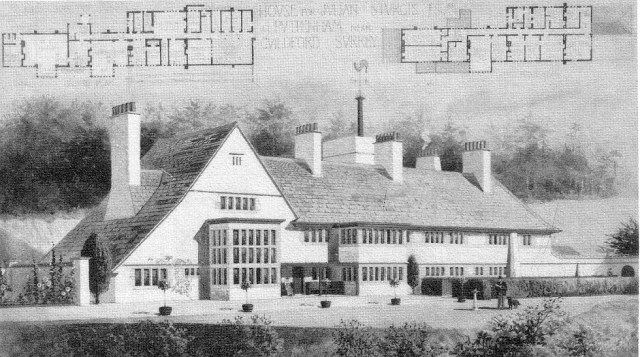

The James Bond movie Spectre has appeared on DvD in the supermarket so I bought it and rewatched it. It measured up very well on re-viewing. I like the helicopter scene coming in over the Porta San Pancrazio with the Villa Aurelia on the left. A bit later I was wondering how it was that he was driving the Aston Martin in Rome, before I realised that this shot was to establish that he had driven there all the way from London. This is what Fleming’s Bond would have done: in On His Majesty’s Secret Service he drives through the night in the Bentley from Spain up the west coast of France past Biarritz. That would have made sense in terms of time management in the 1950s: the 2015 Bond must have a less hectic schedule if he can afford to take the time not to fly. (And M never stops his passport, however out of favour he might be.) And all to use it just once and dump it in the Tiber next to the Ponte Sisto just because there is a bit of an obstacle in the way? Interesting how the Tiber embankments modulate at one point into a Brooklands’-type ‘wall-of-death’. Never noticed that. And it is rather disconcerting the way he drives out of Rome to Blenheim palace! Vanbrugh (who never went to Italy) would have been pleased that he created an English palace grander than anything to be found in Rome!

What I liked about it was the way it picked up all the loose ends of the previous three movies (or two: we will forget about Quantum of Solace) and wove them into a coherent whole. It is like the ‘universes’ now de rigeur with superhero movies. Such as the Japanese gambler at the card table in Casino Royale who turns up as one of Blofeld’s henchmen. All the world’s crime, and all the previous movies turn out to have been orchestrated by Blofeld. Some critics found Blofeld to be too low key, but I think that was right, as it makes a point about the ordinariness of evil. He has to match the bureaucratic evil of Andrew ‘Moriarty’ Scott’s C, and not upstage him as a bizarre character. Someone asks what C gets out of it: it is not money, he is just a true believer, as is Blofeld. That sums up the psychology of many neoliberal politicians: they are not (necessarily) taking kickbacks (though I wouldn’t be too sure): they are true believers in the cause. It was clever to have the two parallel villains (who turn out to be part of the same villainy in the end). C you can believe in as a true villain of our times and someone genuinely dangerous. Blofeld is much more retro, a villain-type that has lost its power to threaten us because it has been made over-familiar from endless previous Bond villains. So Blofeld is quietly normal — as much as a super villain can be — and carries all the retro touches: the white cat, the lair, the boardroom. The villain’s lair is hard to swallow these days with Google maps, which seems to have poor coverage of the Sahara as it is only noticeable in MI6 satellite photos. Not to mention the fact that Morocco is an open country and passing tourists would have noticed. Whatever.

I liked the way this was an intensely moral movie. Everyone who is not a villain has complete personal integrity. M and Moneypenny are wholly likeable, and Moneypenny — Naomie Harris who is fun to watch and gets some good lines — is the modern professional woman who has a life (as Bond discovers when he rings her and she is with her boyfriend.) Bond is presented as being morally compromised because he is a hitman. Whereas in Roger Moore Bond movies he is the go-to man if you need to save the world, here Daniel Craig’s Bond is just a run-of-the-mill maverick hit man who saves the world by being totally professional and having integrity. Lea Seydoux interrogates him in a nice piece of dialogue that attempts to explain why he became what he is: the answer seems to be circumstances at the beginning, after which it is just momentum. Which probably sums it up for most people.

The major theme turns out to be the morality, or amorality, of the hit man. I can’t understand all the talk in the media at the time about the next Bond movie and whether Daniel Craig will be in it. The narrative makes this impossible. It is quite explicit that Lea Seydoux turns him from the ‘dark side’, and they go off together to civilian life, or at least life where he is not in the business of killing people. This morality I find quite refreshing. It makes me think of The Big Country, with its post World War 2 pacifist message, where the hero ‘has the strength not to fight’. That may not sound like Bond, but the fact that, through a good woman, he undergoes a conversion, is intriguing in this genre. Heros have been getting steadily nastier for half a century; indeed, it seems that the heroes in non superhero movies have been getting progressively nastier for half a century. It is an antidote to Tarantino movies, which I find morally repulsive: gratuitous splattering killing, ‘but that’s OK, it is just playing with movie genres’. In fact it is a much nicer movie, morally speaking, than the Dressmaker, which, while presenting itself as social comedy, turns nasty at the end in what critics seemed to think was a clever Tarantinoesque twist but which I though made a complete mess of the movie and left a bad taste in your mouth. Incidentally, the chronology of these four movies, curiously, means that Bond hasn’t in fact killed many people. The arc of time from Casino Royale, where he has just become an 007, and Spectre seems to be only a few months.

And that brings us to the female characters which are handled here better than in any other Bond movie. What made Casino Royale work is that there was a real frisson between Bond and Vesper Lynn, who is his true love, but it ends tragically, in a very silly ending involving sinking Venetian palaces. Again ignoring Quantum of Solace as irrelevant, in Skyfall it is all about Bond’s relationship with his substitute mother, M, and to a lesser extent his workplace colleague, Moneypenny. In Spectre Bond learns to move on and fall in love again. Bond’s behaviour towards all the women he meets is impeccable. In Mexico city he is with someone who has nothing to do with the plot whom he presumably met there. They are about to have sex but the celibate professional puts this aside to go off and do his true job, which is to assassinate someone. This is bit hard on her I guess since she is all wound up and ready to go, but no-one gets hurt. A criticism of other Bond movies and of Fleming is that Bond is the cause of the death of the doomed Bond girl by having sex with her. Here, however, the doomed woman, Monica Bellucci, is doomed (or so it is implied) not because she has sex with Bond (although ultimately his actions in killing her husband doom her, but that has nothing to do with the sex). In fact Bond has sex with her to console her, in a kind of Liebestod.

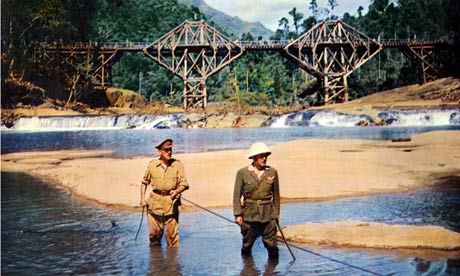

The Lea Seydoux character is very well handled. All Fleming’s women are damaged in some way, which is why they are often doomed. But although she is brought up in circumstances that should have damaged here — the daughter of a hitman and involuntary childhood witness to the violence that is a consequence of this — she is strong-minded and rises above this so that when Bond meets her she has an important career and is wholly functional. She makes it clear she despises what he does because she knows all about it and never flinches from this. She is much tougher than Vesper Lynd, who in the shower scene traumatised to learn what Bond’a life is really all about. When she does come out fighting in the train it is because she has no choice, and gets no sadistic pleasure from it. This doesn’t mean she doesn’t get turned on by the fight, and after it she and Bond have passionate sex. This is very Fleming, and is the main theme of The Spy Who Loved Me (the book). But only up to a point. There the female lead gets turned on by Bond because he is a macho killer. Here it is more like a scene in Mary Renault’s The Bull from the Sea, where Theseus and Araiadne, having just escaped the collapse of the Labyrinth/Knossos in an earthquake, make love on the ground there and then because their blood is up from the excitement of just escaping death. And, of course, they have been falling for each other for a while. All this takes place on a train, the preferred site of URST moments ever since North by Northwest, including Casino Royale. Here however the verbal sparring which ought to be central to the train scene is shifted to an earlier moment in the hotel L’Américan, where she tells Bond in so uncertain terms that she is not going to fall into his arms just because her father has been killed and you had better not touch me. As result there is not enough of her sashaying into the dining car in her evening dress showing off her very excellent figure and wrestling verbally with him. (Although there is the scene about the gun.) The heavy arrives too quickly. The resulting fight is surely a homage to the movie of From Russia with Love, and the heavy has the same robotic efficiency as there. But if only trains were really like that! Once upon a time you could get a three course set menu with linen tablecloths on Italian trains crossing the Alps, and the Talgo from Chambéry to Barcelona, no doubt long gone, once had a wonderful formal dining car and big plush seats. But I bet there is nothing like this in Morocco! Or anywhere else any more. And dressing for dinner in dinner suit and slinky gown? If only!

And for a Bond movie the action sequences are surprisingly well integrated into the plot, although the genre requires that they be digressive. Even the lengthy Mexico city pre-credit sequence is less of a standalone tour-de-force and makes more sense in moving the plot along that the equivalent in Casino Royale. The plane in the Austrian mountain sequences, however, was pretty silly and didn’t add much. Plane crash stunts never work well — planes just don’t bounce alomg for miles when they crash. A low point is the crash landing in Las Vegas in Con-Air, which I am reminded of a bit here. What does grate is the absence of any consequences of the action. After blowing up half a block in Mexico city Bond can walk around the corner back into the Day of Death parade and people aren’t running in all directions screaming ‘terrorist attack’? Yeah, right. After destroying half the Morocco train it is next morning and Bond and Seydoux are being put quietly let off in their days clothes in a halt in the middle of nowhere as if nothing had happened? And you can shoot down a helicopter with a pistol from half a mile away? That said, I thought the ending on the bridge in London was not bad, even if a few plot devices were clunky – such as Lea Seydoux just happening to make herself heard in time to be rescued before MI6 headquarters blows up.

Irrelevant analogy of the week.

Irrelevant analogy of the week.

There are some amazing late gothic and art deco doorways here as well, but that is for another time. Like Krakow itself (before it was ruined by drunken youths from Northern Europe on cheap weekend booze-ups), they are evocative of the depths of central Europe, a long, long time ago, with the tartars/cossacks about to arrive at any moment from the steppes. They are everything that constipated classicism is not, and, since our subconscious architectural aesthetic still suffers from neoclassical/modernist constipation, they are generally considered not appropriate to serious architecture.

There are some amazing late gothic and art deco doorways here as well, but that is for another time. Like Krakow itself (before it was ruined by drunken youths from Northern Europe on cheap weekend booze-ups), they are evocative of the depths of central Europe, a long, long time ago, with the tartars/cossacks about to arrive at any moment from the steppes. They are everything that constipated classicism is not, and, since our subconscious architectural aesthetic still suffers from neoclassical/modernist constipation, they are generally considered not appropriate to serious architecture.

This seems to be of pressed metal, and, as at Schloss Ambras there is a tongue, which probably has a functional purpose to make the water flow out of the centre of the mouth. The dragon is crowned, and there is a kind of rudimentary tail or body curving up behind. There is a cross-form at the end; I am not sure if its is meant to be bent down like this. The wings are riveted on. Because of the extended overhang of the eaves, the pipe part is not very long. The wrought iron brace is much simpler than at Schloss Ambras, and very elegant (Fig. 6).

This seems to be of pressed metal, and, as at Schloss Ambras there is a tongue, which probably has a functional purpose to make the water flow out of the centre of the mouth. The dragon is crowned, and there is a kind of rudimentary tail or body curving up behind. There is a cross-form at the end; I am not sure if its is meant to be bent down like this. The wings are riveted on. Because of the extended overhang of the eaves, the pipe part is not very long. The wrought iron brace is much simpler than at Schloss Ambras, and very elegant (Fig. 6).

The head seems to be of beaten metal, with wonderful ‘ears’ behind. These are very delicately made in sheet metal that seems to have been beaten over a form to get the ridges in the curved leaves, which are like the plumes of baroque stage costume (Fig. 8).

The head seems to be of beaten metal, with wonderful ‘ears’ behind. These are very delicately made in sheet metal that seems to have been beaten over a form to get the ridges in the curved leaves, which are like the plumes of baroque stage costume (Fig. 8).

Re-viewing Spectre

The James Bond movie Spectre has appeared on DvD in the supermarket so I bought it and rewatched it. It measured up very well on re-viewing. I like the helicopter scene coming in over the Porta San Pancrazio with the Villa Aurelia on the left. A bit later I was wondering how it was that he was driving the Aston Martin in Rome, before I realised that this shot was to establish that he had driven there all the way from London. This is what Fleming’s Bond would have done: in On His Majesty’s Secret Service he drives through the night in the Bentley from Spain up the west coast of France past Biarritz. That would have made sense in terms of time management in the 1950s: the 2015 Bond must have a less hectic schedule if he can afford to take the time not to fly. (And M never stops his passport, however out of favour he might be.) And all to use it just once and dump it in the Tiber next to the Ponte Sisto just because there is a bit of an obstacle in the way? Interesting how the Tiber embankments modulate at one point into a Brooklands’-type ‘wall-of-death’. Never noticed that. And it is rather disconcerting the way he drives out of Rome to Blenheim palace! Vanbrugh (who never went to Italy) would have been pleased that he created an English palace grander than anything to be found in Rome!

What I liked about it was the way it picked up all the loose ends of the previous three movies (or two: we will forget about Quantum of Solace) and wove them into a coherent whole. It is like the ‘universes’ now de rigeur with superhero movies. Such as the Japanese gambler at the card table in Casino Royale who turns up as one of Blofeld’s henchmen. All the world’s crime, and all the previous movies turn out to have been orchestrated by Blofeld. Some critics found Blofeld to be too low key, but I think that was right, as it makes a point about the ordinariness of evil. He has to match the bureaucratic evil of Andrew ‘Moriarty’ Scott’s C, and not upstage him as a bizarre character. Someone asks what C gets out of it: it is not money, he is just a true believer, as is Blofeld. That sums up the psychology of many neoliberal politicians: they are not (necessarily) taking kickbacks (though I wouldn’t be too sure): they are true believers in the cause. It was clever to have the two parallel villains (who turn out to be part of the same villainy in the end). C you can believe in as a true villain of our times and someone genuinely dangerous. Blofeld is much more retro, a villain-type that has lost its power to threaten us because it has been made over-familiar from endless previous Bond villains. So Blofeld is quietly normal — as much as a super villain can be — and carries all the retro touches: the white cat, the lair, the boardroom. The villain’s lair is hard to swallow these days with Google maps, which seems to have poor coverage of the Sahara as it is only noticeable in MI6 satellite photos. Not to mention the fact that Morocco is an open country and passing tourists would have noticed. Whatever.

I liked the way this was an intensely moral movie. Everyone who is not a villain has complete personal integrity. M and Moneypenny are wholly likeable, and Moneypenny — Naomie Harris who is fun to watch and gets some good lines — is the modern professional woman who has a life (as Bond discovers when he rings her and she is with her boyfriend.) Bond is presented as being morally compromised because he is a hitman. Whereas in Roger Moore Bond movies he is the go-to man if you need to save the world, here Daniel Craig’s Bond is just a run-of-the-mill maverick hit man who saves the world by being totally professional and having integrity. Lea Seydoux interrogates him in a nice piece of dialogue that attempts to explain why he became what he is: the answer seems to be circumstances at the beginning, after which it is just momentum. Which probably sums it up for most people.

The major theme turns out to be the morality, or amorality, of the hit man. I can’t understand all the talk in the media at the time about the next Bond movie and whether Daniel Craig will be in it. The narrative makes this impossible. It is quite explicit that Lea Seydoux turns him from the ‘dark side’, and they go off together to civilian life, or at least life where he is not in the business of killing people. This morality I find quite refreshing. It makes me think of The Big Country, with its post World War 2 pacifist message, where the hero ‘has the strength not to fight’. That may not sound like Bond, but the fact that, through a good woman, he undergoes a conversion, is intriguing in this genre. Heros have been getting steadily nastier for half a century; indeed, it seems that the heroes in non superhero movies have been getting progressively nastier for half a century. It is an antidote to Tarantino movies, which I find morally repulsive: gratuitous splattering killing, ‘but that’s OK, it is just playing with movie genres’. In fact it is a much nicer movie, morally speaking, than the Dressmaker, which, while presenting itself as social comedy, turns nasty at the end in what critics seemed to think was a clever Tarantinoesque twist but which I though made a complete mess of the movie and left a bad taste in your mouth. Incidentally, the chronology of these four movies, curiously, means that Bond hasn’t in fact killed many people. The arc of time from Casino Royale, where he has just become an 007, and Spectre seems to be only a few months.

And that brings us to the female characters which are handled here better than in any other Bond movie. What made Casino Royale work is that there was a real frisson between Bond and Vesper Lynn, who is his true love, but it ends tragically, in a very silly ending involving sinking Venetian palaces. Again ignoring Quantum of Solace as irrelevant, in Skyfall it is all about Bond’s relationship with his substitute mother, M, and to a lesser extent his workplace colleague, Moneypenny. In Spectre Bond learns to move on and fall in love again. Bond’s behaviour towards all the women he meets is impeccable. In Mexico city he is with someone who has nothing to do with the plot whom he presumably met there. They are about to have sex but the celibate professional puts this aside to go off and do his true job, which is to assassinate someone. This is bit hard on her I guess since she is all wound up and ready to go, but no-one gets hurt. A criticism of other Bond movies and of Fleming is that Bond is the cause of the death of the doomed Bond girl by having sex with her. Here, however, the doomed woman, Monica Bellucci, is doomed (or so it is implied) not because she has sex with Bond (although ultimately his actions in killing her husband doom her, but that has nothing to do with the sex). In fact Bond has sex with her to console her, in a kind of Liebestod.

The Lea Seydoux character is very well handled. All Fleming’s women are damaged in some way, which is why they are often doomed. But although she is brought up in circumstances that should have damaged here — the daughter of a hitman and involuntary childhood witness to the violence that is a consequence of this — she is strong-minded and rises above this so that when Bond meets her she has an important career and is wholly functional. She makes it clear she despises what he does because she knows all about it and never flinches from this. She is much tougher than Vesper Lynd, who in the shower scene traumatised to learn what Bond’a life is really all about. When she does come out fighting in the train it is because she has no choice, and gets no sadistic pleasure from it. This doesn’t mean she doesn’t get turned on by the fight, and after it she and Bond have passionate sex. This is very Fleming, and is the main theme of The Spy Who Loved Me (the book). But only up to a point. There the female lead gets turned on by Bond because he is a macho killer. Here it is more like a scene in Mary Renault’s The Bull from the Sea, where Theseus and Araiadne, having just escaped the collapse of the Labyrinth/Knossos in an earthquake, make love on the ground there and then because their blood is up from the excitement of just escaping death. And, of course, they have been falling for each other for a while. All this takes place on a train, the preferred site of URST moments ever since North by Northwest, including Casino Royale. Here however the verbal sparring which ought to be central to the train scene is shifted to an earlier moment in the hotel L’Américan, where she tells Bond in so uncertain terms that she is not going to fall into his arms just because her father has been killed and you had better not touch me. As result there is not enough of her sashaying into the dining car in her evening dress showing off her very excellent figure and wrestling verbally with him. (Although there is the scene about the gun.) The heavy arrives too quickly. The resulting fight is surely a homage to the movie of From Russia with Love, and the heavy has the same robotic efficiency as there. But if only trains were really like that! Once upon a time you could get a three course set menu with linen tablecloths on Italian trains crossing the Alps, and the Talgo from Chambéry to Barcelona, no doubt long gone, once had a wonderful formal dining car and big plush seats. But I bet there is nothing like this in Morocco! Or anywhere else any more. And dressing for dinner in dinner suit and slinky gown? If only!

And for a Bond movie the action sequences are surprisingly well integrated into the plot, although the genre requires that they be digressive. Even the lengthy Mexico city pre-credit sequence is less of a standalone tour-de-force and makes more sense in moving the plot along that the equivalent in Casino Royale. The plane in the Austrian mountain sequences, however, was pretty silly and didn’t add much. Plane crash stunts never work well — planes just don’t bounce alomg for miles when they crash. A low point is the crash landing in Las Vegas in Con-Air, which I am reminded of a bit here. What does grate is the absence of any consequences of the action. After blowing up half a block in Mexico city Bond can walk around the corner back into the Day of Death parade and people aren’t running in all directions screaming ‘terrorist attack’? Yeah, right. After destroying half the Morocco train it is next morning and Bond and Seydoux are being put quietly let off in their days clothes in a halt in the middle of nowhere as if nothing had happened? And you can shoot down a helicopter with a pistol from half a mile away? That said, I thought the ending on the bridge in London was not bad, even if a few plot devices were clunky – such as Lea Seydoux just happening to make herself heard in time to be rescued before MI6 headquarters blows up.